The benefits of placemaking in urban design

Andrew Hoyne caught up with Urban.com to discuss how effective placemaking approaches can result in significant social and economic benefits long-term.

Urban.com.au: Thank you Andrew for taking the time to chat with me today. The concept of ‘placemaking’ is a fascinating one, and I could imagine that without a precursor, people could quickly develop their own meaning of the term. How do you describe the essence of ‘placemaking’?

Andrew Hoyne: The essence of placemaking is about creating great experiences for people. Placemaking is the curation and creation of the hard and soft experiences, that ensure people are magnetically drawn to a space. Both built form and space activation. By stimulating positive experiences, you make a place destinational. It’s about how you give real meaning and purpose to a place, that compels people to care, engage and repeatedly visit. You need to begin by analysing community’s unique needs. So you must ask what already exists and what is missing. It’s the consideration of all the elements that work together to create a compelling destination: planning, architecture, materiality, green space, amenity, infrastructure, art and cultural connections. So good placemaking begins and ends by considering people who will use and inhabit a space. Good placemaking results in better social and economic outcomes for everyone.

U: In this video, you mention that the goal is to plan out 10-30 years ahead. Given the fluidity and uncertainty of the property market, what is your strategy for future development planning?

AH: In the context of that quote I’m actually talking about place or city branding, rather than property development. Today it is vital that cities think 20-30 years ahead if they want to ensure that their city remains competitive with an edge on their rivals. We’ve seen this already with cities like Berlin, Dublin, Copenhagen and London; they’ve all shown how a compelling place brand can future-proof your city, ensuring its success, and the success of its residents for decades to come. But a place brand does have a direct impact on the development industry; it will inform the vision for the future of the city and as a result dictate how it evolves and grows. So it’s really important to have that long term plan in place to ensure the built environment is bringing an agreed vision to life. The great thing with a strong place brand is that it functions like magnetic north for a city; you may get slightly blown off course by say a downturn in the property market, but you always have this set of guiding principles to realign to. This ensures you’re working towards that end goal of what the city will one day become and not floundering and changing tack with every economic bump. So to a certain extent the core principles of the place brand should be driving the market, rather than the other way around.

U: Do you feel as though developers and town planners have an element of control over shaping the future of our cities? Or do they evolve more organically?

AH: Today developers and planners, along with architects and government, do indeed have the great privilege and the responsibility of shaping the future of our cities. That’s why it’s so vital they begin the development process with a strong Place Vision in place. A Place Visioning TM process creates a blueprint that guides and shapes a space, regardless of size. Resolving this early, before you’ve even begun to talk about built form, is fundamental to successfully identifying anchors and establishing the ‘magnets’ (amenity; public realm; retail; F&B) that will attract people to a place, precinct or city. Done well it mitigates risk and results in developments and cities that are socially and economically successful.

U: One of the core aims of ‘placemaking’ is to create more meaningful spaces. What design features can you add to a space to create a more meaningful experience for its users?

AH: There is no set list of features, but there is a design thinking framework you can use to create meaningful spaces. This begins with getting boots on the ground and finding out what makes a place tick. Visit the suburb or site, talk to the locals, sit in the cafes and then ask “what role can this development fulfil in this community?”. You then need to either understand your multi-faceted target audience, or define it. Once you’re clear on your various ‘tribes’, compare their needs and desires to the experience gaps for that location. Once you clearly understand your audience, and have a sense of the experience gaps, it’s time to build the business case and articulate the Place Vison. You then start by bringing the vision to life through early activation so assets and experiences grow from an early phase, rather than waiting for completion and pulling the fence down, so to speak. This is a great way to engage the community from the get go. Finally, you need to follow through and maintain engagement through careful curation, activation and stakeholder management.

U: Which of Australia’s key suburbs do you think have the strongest sense of community and how do you think other areas can mirror their success?

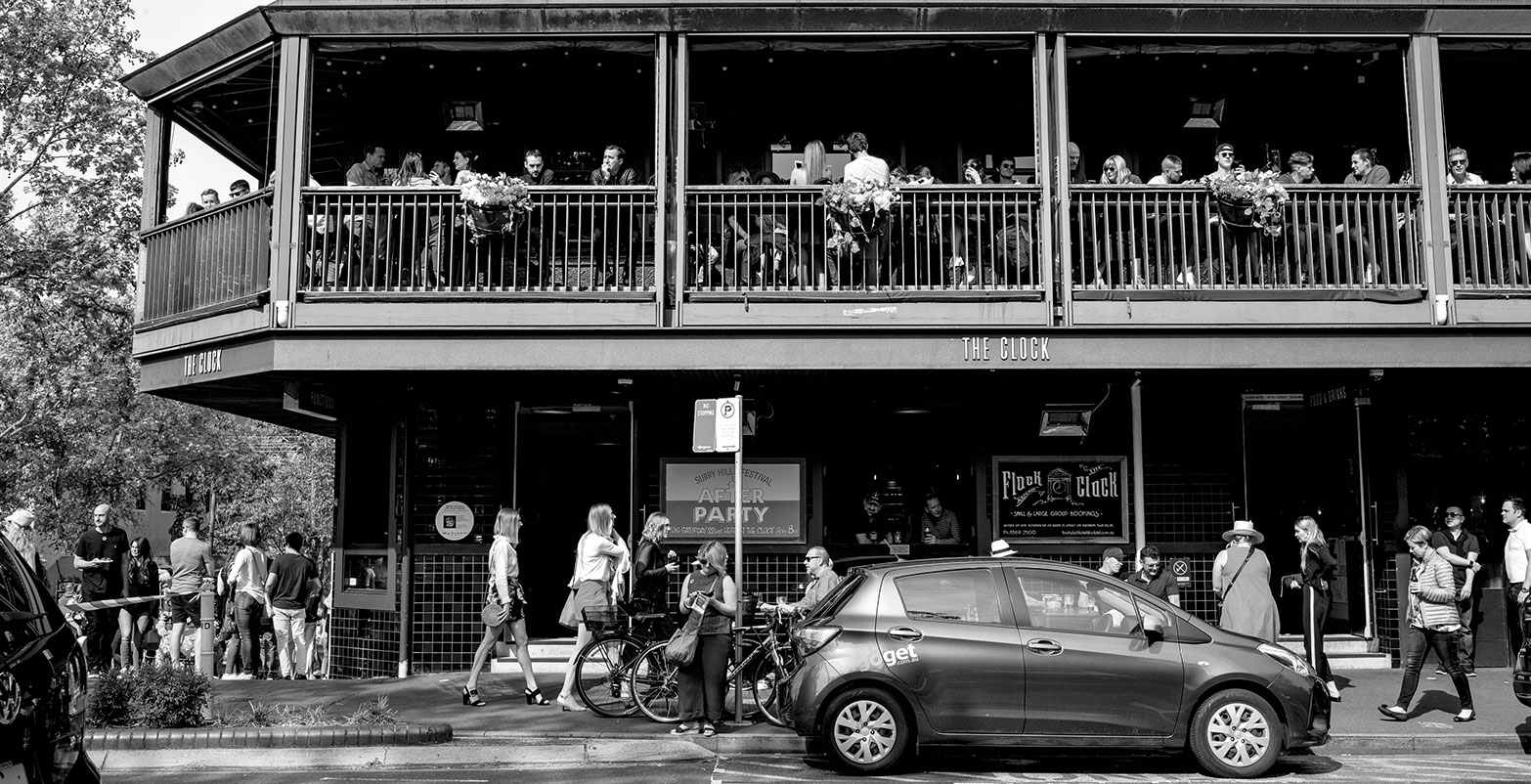

AH: I’m lucky enough to live in Surry Hills which I think has a phenomenal sense of community. Less than 15 years ago, the broader population thought Surry Hills was “too dirty and too dangerous” but over the last decade it’s become so famous it was listed as one of the top 30 places in the world to live. To this day it has an incredibly creative energy that has spawned the birth of famous businesses and experiences. It’s got great schools, restaurants, bars and shops; public transport is phenomenal, and everything is walkable. Ultimately it’s suburbs like Surry Hills that give Sydney it’s village character. While I think it’s very unwise to suggest other suburbs try to replicate Surry Hills, I think other areas can mirror its success by developing, elevating and promoting their own unique DNA – that makes it a great place for their locals. It all comes back to people and my view is that if you create experiences that fulfil the needs of the community it will always be a success. Surry Hills supports its local community first and foremost in nearly everything it does, and that in my view is how to succeed.

U: What was the process before ‘placemaking’ and how do you feel the concept is changing industry norms? Is there scope for developers and investors to reach a higher ROI if they follow your planning approach?

AH: Placemaking has been around since the 1960’s, although it’s been through lots of change. Up until recently, most people working in the space were focussed single mindedly on creating community oriented spaces. There was no real consideration for economic benefit, and in fact many were appalled at the idea of any form of commercialisation. However, our strong view has always been that someone has to pay for the upkeep, maintenance, constant improvement, activation and evolution over time. It’s rare that federal, state or local governments have this perspective which means that good intentions often result in spaces that degrade over time. A commercial approach ensures spaces are taken care of and loved, so people keep coming back. It’s benefiting the industry enormously because it has given us a way of creating socially and economically successful places, that meet the needs of the community, and ensure increased upside for developers and investors. This philosophy underpins everything we do: if you deliver a superior solution for the community, you generate stronger financial returns. One of my favourite developments of the moment is Industry City in Brooklyn, which is a great example of all this. It’s actually a commercial precinct that was aimed at the innovation economy but it’s been so perfectly curated with such a great mix of all these elements that it’s become a magnet and people visit from all over the world. Because of this success the average property price in the neighbourhood in which the development sits, Sunset Park, has risen by 43 per cent since the third quarter of 2014. And the price per square foot has risen to an all-time high level of growth which far outstrips wider Brooklyn. Lonely Planet has now named Sunset Park among the world’s 10 “coolest neighbourhoods”. This is an example of being rewarded for delivering what the market wants. This approach also mitigates risk. Traditionally, mitigating risk meant doing the same thing you had always done, because you knew that it made money. These days this is the riskiest thing you can do because it will not capture the attention of a more sophisticated market with increasingly higher expectations. No one will line up, pay a premium, or celebrate the arrival of another cookie-cutter development, which doesn’t address the needs of a community or provide tangible societal benefits. The only way to mitigate risk is to ask ourselves: ‘What is it we can do to make these communities stronger and more enjoyable?’, ‘What is missing and how can our development provide that?’. If you do this and create a compelling solution that exceeds people’s expectations, you will ensure stronger sales and returns than the rest of the industry. A great thinker Alan Fletcher once said “Fish are the last to recognise water.” I fear the same can be true in development. We need to break out of the old way of doing things, to create more engaging outcomes for communities and businesses. So creating magnetic destinations is mandatory to ensure a place has competitive advantage, whether it’s a mixed use precinct, or an entire city.

U: Your place and property agency Hoyne strives to deliver ‘Brave not beige’ campaigns. What’s been your bravest (or favourite) campaign yet?

AH: One of our bravest campaigns has been Wonderland, the final release at Central Park for Frasers Property. Rather than presenting traditional property clichés the campaign identity took its creative cues from the world of retail which was a really unusual and daring approach. When we were looking at Central Park as a precinct, with it’s incredible mix of heritage and modern architecture, laneways, bars and restaurants that draw you into explore, it struck us that living there is like living in a modern day wonderland. So we brought the precinct and the development to life through a contemporary take on Lewis Carroll’s novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. A combination of CGI and photography was used to create these cool visual montages, unlike anything else in the Australian property marketplace – they fully embraced the journey and the storytelling experience. It was a bold move and there were a lot of raised eyebrows at the start but Frasers were incredible and gave it their full support. And it paid off; the results were phenomenal with 1,700 enquiries before launch and $140million worth of sales at launch, before a complete sell-out. But great solutions are always achieved by real collaboration. And as Ken Blanchard famously said “None of us is as smart as all of us.”

U: In a perfect world, what would your dream suburb/precinct look like?

AH: My dream suburb or precinct would have great experiences for people of all ages. From kids, adults and the aged. It would have a unique sense of character and community. It would make the most of the area’s history and heritage. There would be great bars and awesome restaurants. It would have beautiful green spaces where people could hang out, and kids could ride their bikes. There’d be great public transport links. People would be able to walk their kids to school in the mornings. Everyone would walk to work. It would facilitate improved outcomes for business, innovation and creativity. And there would be something unexpected there, which you couldn’t find anywhere else. It could be built form, it could be art, or it could be a service. But it would be the central thing the space would become famous for.

U: Lastly, with the effects of climate change requiring critical attention, what do you believe is the best response to aid in alleviating the problem when it comes to developing our cities?

AH: As the futurist Peter Ellyard said to me “sustainability means creating zero net collateral harm”. In fact, he said this can be applied to personal relationships, health, design, and actions by government. Or as Peter summed up, “The decisions I make, and the things I do, do not hurt you”. The best way for development to mitigate our environmental impact is to create built form that has meaningful legacy and longevity. I believe we also need to think more creatively about how we use old buildings, rather than reducing them to a pile of rubble if they don’t instantly suit the need of the moment. I love the quote by Stephanie Meeks (CEO and President of the National Trust for Historic Preservation), that “the greenest building, is the one which is already built”. Her team at the National Trust in the USA have mapped historic and new buildings in 50 cities around the world to see how individual blocks performed. They actually discovered that blocks which have a mix of old and new buildings have more small businesses, more women-and minority-owned businesses, are denser and have more affordable housing units. I also think that old buildings make great incubators for small business because they provide flexible spaces that help these businesses prosper.

This article was originally published on Urban.com.au.